A Clockwork Orange is a cautionary tale. Even within the story, the meta moment warned our narrator of the future to come. In a time of glorifying violence through the ease of technology, A Clockwork Orange seems to be a prevalent story to share. In Hubris Theatre Company's production of the play written by the novelist himself, the stage adaptation of Anthony Burgess' dystopian thriller is a haunting violence-laden drama about the minds of the future and the corruption of changing their ways.

Like the novel, Burgess uses Alex DeLarge to narrate his own story. Alex is a leader of a trio of droogs who spend their nights engaging in acts of ultra-violence that terrorizes anyone in their path. When a mutiny forms due to Alex's manner, he is set up for a crime that leads him to be imprisoned. While detained, Alex is used as a Ludovico aversion therapy test suspect that hopes to reform the minds of the corrupt youth. But when the project is completed and Alex begins to have adverse reactions to violence, the question of government corruption is called into play. The film version of A Clockwork Orange is a well-revered classic so putting a unique spin on a stage adaptation while still paying homage to the audience favorite is crucial. Director John Bateman surely has a fondness to Burgess’ story. And it's quite an ambitious undertaking to bring this piece to life. But from a theatrical standpoint, Bateman ran into many problems that altered the storytelling. A Clockwork Orange starts off with a bang. A very brief introduction leads to the first display of ultra violence. The structure of the text overlaps the violence with some crucial bit of text. Unfortunately, Bateman seemed to focus his attention on the fight work pulling the audience away from the dialogue. There's no denying that the choreography by Frank Alfano Jr. is quite impressive but shock value should not trump content. And sadly, this was foreshadow of what was to come. Bateman's production had so much going on that some intent was lost. Incorporating modern touches helped bring the story into this generation. In an age where technological advances have been incorporated into theater, it's natural to want to utilize them if you have the resources. Bateman utilized two televisions that played a loop during Alex's aversion therapy. The trouble was they did not line up to Dr. Brodsky's dialogue thus losing the impact. It's more striking to have Dr. Brodsky paint a vivid picture that the audience has to visually create as opposed to incorporating attention-stealing shock value.

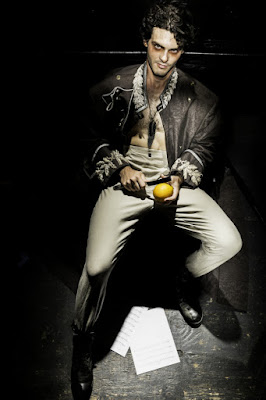

To take in such an iconic role as Alex DeLarge is no easy task. And without a doubt, you have to give Alex Tissiere immense credit for diving into the complexities of this person. But Tissiere's characterization ultimately hurt his performance. Between intricate nuances in diction and a British accent, Tissiere's clarity suffered. And it's a shame because there was vast potential in his portrayal. While it was hard to hear the change, you could see a switch in character through his journey. Another with diction issues was Sam Finn Cutler as Dim. Most of his dialogue was incomprehensible. Rounding out the droog, Steven Bono Jr. and Luke Wehner as George and Pete were some of the strongest all-around actors on stage. Both Bono and Wehner had strong journeys and created good oppositions for Alex by the end. Though in the scope of the three-hour epic her presence was limited, Kate Parker’s Dr. Brodsky was dominant and compelling. The way she controlled the Ludovico scenes was some of the strongest of the piece. Donal Brophy as F. Alexander brought much humanity following his welcoming of Alex in Act II. His struggle though was playing the reveal too soon.

Roy Arias Stage 7 Sage Theater is a very specific space and scenic designer Scott Tedmon-Jones expertly transforming the stage into Burgess’ world. Utilizing a blended feel of metal and wood and marrying the architecture of the theater, Tedmon-Jones created a brilliant concept for Bateman. That being said, the moving parts that Bateman had caused some transition blunders. Lighting designer Sarah Huyck utilized Tedmon-Jones’ design wonderfully. Going beyond warm and cool, Huyck’s use of and lack of color had a direct effect on the mood of the play. Though orange may have been an on-point color for the play, it was impactful. The soundtrack that accompanied many of the brutal scenes helped add a juxtaposition in this world but the sound levels may have needed a little bit of assistance and it was too loud the majority of the piece.

Hubris Theatre Company’s production of A Clockwork Orange was nothing short of ambitious. And you must commend them for that. Despite a recognizable story, clarity is key and the storytelling in this production was unclear.

Like the novel, Burgess uses Alex DeLarge to narrate his own story. Alex is a leader of a trio of droogs who spend their nights engaging in acts of ultra-violence that terrorizes anyone in their path. When a mutiny forms due to Alex's manner, he is set up for a crime that leads him to be imprisoned. While detained, Alex is used as a Ludovico aversion therapy test suspect that hopes to reform the minds of the corrupt youth. But when the project is completed and Alex begins to have adverse reactions to violence, the question of government corruption is called into play. The film version of A Clockwork Orange is a well-revered classic so putting a unique spin on a stage adaptation while still paying homage to the audience favorite is crucial. Director John Bateman surely has a fondness to Burgess’ story. And it's quite an ambitious undertaking to bring this piece to life. But from a theatrical standpoint, Bateman ran into many problems that altered the storytelling. A Clockwork Orange starts off with a bang. A very brief introduction leads to the first display of ultra violence. The structure of the text overlaps the violence with some crucial bit of text. Unfortunately, Bateman seemed to focus his attention on the fight work pulling the audience away from the dialogue. There's no denying that the choreography by Frank Alfano Jr. is quite impressive but shock value should not trump content. And sadly, this was foreshadow of what was to come. Bateman's production had so much going on that some intent was lost. Incorporating modern touches helped bring the story into this generation. In an age where technological advances have been incorporated into theater, it's natural to want to utilize them if you have the resources. Bateman utilized two televisions that played a loop during Alex's aversion therapy. The trouble was they did not line up to Dr. Brodsky's dialogue thus losing the impact. It's more striking to have Dr. Brodsky paint a vivid picture that the audience has to visually create as opposed to incorporating attention-stealing shock value.

To take in such an iconic role as Alex DeLarge is no easy task. And without a doubt, you have to give Alex Tissiere immense credit for diving into the complexities of this person. But Tissiere's characterization ultimately hurt his performance. Between intricate nuances in diction and a British accent, Tissiere's clarity suffered. And it's a shame because there was vast potential in his portrayal. While it was hard to hear the change, you could see a switch in character through his journey. Another with diction issues was Sam Finn Cutler as Dim. Most of his dialogue was incomprehensible. Rounding out the droog, Steven Bono Jr. and Luke Wehner as George and Pete were some of the strongest all-around actors on stage. Both Bono and Wehner had strong journeys and created good oppositions for Alex by the end. Though in the scope of the three-hour epic her presence was limited, Kate Parker’s Dr. Brodsky was dominant and compelling. The way she controlled the Ludovico scenes was some of the strongest of the piece. Donal Brophy as F. Alexander brought much humanity following his welcoming of Alex in Act II. His struggle though was playing the reveal too soon.

Roy Arias Stage 7 Sage Theater is a very specific space and scenic designer Scott Tedmon-Jones expertly transforming the stage into Burgess’ world. Utilizing a blended feel of metal and wood and marrying the architecture of the theater, Tedmon-Jones created a brilliant concept for Bateman. That being said, the moving parts that Bateman had caused some transition blunders. Lighting designer Sarah Huyck utilized Tedmon-Jones’ design wonderfully. Going beyond warm and cool, Huyck’s use of and lack of color had a direct effect on the mood of the play. Though orange may have been an on-point color for the play, it was impactful. The soundtrack that accompanied many of the brutal scenes helped add a juxtaposition in this world but the sound levels may have needed a little bit of assistance and it was too loud the majority of the piece.

Hubris Theatre Company’s production of A Clockwork Orange was nothing short of ambitious. And you must commend them for that. Despite a recognizable story, clarity is key and the storytelling in this production was unclear.